Pigs play a very important role among the people of Papua (former Dutch New Guinea), and especially so among those living in the Central Highlands. Apart from pigs and deer, originally brought in by the Europeans, there are not many mammals on this island. The wild pigs in Papua are similar to those in Dutch national park, but they are skinnier.

Pigs play a very important role among the people of Papua (former Dutch New Guinea), and especially so among those living in the Central Highlands. Apart from pigs and deer, originally brought in by the Europeans, there are not many mammals on this island. The wild pigs in Papua are similar to those in Dutch national park, but they are skinnier. Pigs are not only bred for their meat, but they also represent social values and have even become a status symbol. The more pigs an individual has, the more pigs he can give away, leading to bigger feasts and a higher social status. The killing of pigs is also tied to important events such as cremation, marriage and initiation rites. Pigs are still the main dowry in exchange for women.

Pigs are not only bred for their meat, but they also represent social values and have even become a status symbol. The more pigs an individual has, the more pigs he can give away, leading to bigger feasts and a higher social status. The killing of pigs is also tied to important events such as cremation, marriage and initiation rites. Pigs are still the main dowry in exchange for women.

At the Wissel Lakes, a Dutch attempt to cross pigs from Holland with local ones almost ended up in a disaster. From 1961 to 1969 the Franciscan Sibbele Hylkema lived among the Ngalum in the Star Mountains and a former district officer H.L. Peters lived among the Dani from 1959 to 1964. Both men observed, among other things, the role of pigs in Papua society and wrote about this.

Content:

1. Pigs in the Wissel Lakes District

2. The role of pigs in the Highlands

3. Social status and medium of exchange

4. Pigs as payment for wife

5. Castrating pigs

6. The killing

7. Preparing the meat

8. Dividing the food

9. Links

10. Sources

1. Pigs in the Wissel Lakes District

Joewò, pig celebration, is of great social importance for Papuans. Their wealth depends on the number of pigs they have. For centuries pigs have been the most priced possession for Papuans.

Joewò, pig celebration, is of great social importance for Papuans. Their wealth depends on the number of pigs they have. For centuries pigs have been the most priced possession for Papuans.

When the Dutch arrived in this lake district in the fifties, they wanted to boost development and improve the breeding methods. The Dutch imported their own fat rosy specimens which were much bigger than the local scrawny ones. It was their intention to cross the two species and breed a meatier variety. However, it had disastrous consequences. The  imported pigs carried a virus which contaminated the pigs of the Kepaupu people. The local pig population was almost decimated. This was a catastrophe for two reasons: They are an important status symbol and an important source of protein. The killing of pigs is reserved for special occasions and is accompanied by parties for days on end. Tribes from local areas come in to trade and do deals. These pig celebrations are a highlight on the social calendar of the Kepauku. Thus the high rate of death of their pigs represented a loss of social networking. It did not take long for the whites to be regarded as the bearers of evil spirits, as illness is associated with the anger of such spirits.

imported pigs carried a virus which contaminated the pigs of the Kepaupu people. The local pig population was almost decimated. This was a catastrophe for two reasons: They are an important status symbol and an important source of protein. The killing of pigs is reserved for special occasions and is accompanied by parties for days on end. Tribes from local areas come in to trade and do deals. These pig celebrations are a highlight on the social calendar of the Kepauku. Thus the high rate of death of their pigs represented a loss of social networking. It did not take long for the whites to be regarded as the bearers of evil spirits, as illness is associated with the anger of such spirits.

2.The role of pigs in the Highlands

Among the Dani of the Central Highlands, pigs are significant in a number of ways.

Among the Dani of the Central Highlands, pigs are significant in a number of ways.

In his book ‘Chapters from the socio-religious life of the Dani-community’ (1965) H.L. Peters writes: “ One can’t say the Dani kill pigs for meat. The Dani rarely kill a pig just for eating. The killing and eating of pig meat is always related to important social occasions such as cremation, marriage and initiation rites. An exception to the rule is a pig which is sick or has been stolen, for then they prefer to consume it as fast as possible. The most regularly occurring event at which pig meat is consumed is at a cremation. A special occasion at which pig meat is eaten every day for weeks on end by both men and women as well as children, is during the major pig feast, held at regular intervals. The amount of meat and the rate at which it is consumed, is almost unbelievable”.

About the role of pigs among the Ngalum, S.Hylkema states:” Although it is not customary to refer to the social position of a pig, it is precisely such a position that is assigned to a pig within this society. The pig is subservient to people, but at the same time people are willing to serve the pig. It is actually a much respected creature. The mode of cultivation is largely determined by the presence of the pigs. Because of these animals, people have to plant their main crop, bataten(sweet potatoes), inside a fenced area, while the pigs can roam the whole of the valley and root where they will”. As is the case for the Ngalum, the pigs of the Dani also walk about all day long looking for food. And at night they get bataten, which the women have brought along from their gardens.

About the role of pigs among the Ngalum, S.Hylkema states:” Although it is not customary to refer to the social position of a pig, it is precisely such a position that is assigned to a pig within this society. The pig is subservient to people, but at the same time people are willing to serve the pig. It is actually a much respected creature. The mode of cultivation is largely determined by the presence of the pigs. Because of these animals, people have to plant their main crop, bataten(sweet potatoes), inside a fenced area, while the pigs can roam the whole of the valley and root where they will”. As is the case for the Ngalum, the pigs of the Dani also walk about all day long looking for food. And at night they get bataten, which the women have brought along from their gardens.

3. Social status and medium of exchange

From a social perspective, pigs are very significant. The number of pigs that an individual owns helps to determine his prestige. “An important man, a gain, owns many pigs. A person who does not own any or very few pigs cannot become a gain”, writes Peters. The pig is a medium of exchange: services, personal feats, debts and obligations towards each other are all paid with pigs or pigs meat. The pig also plays a key role in religious ceremonies for which one or more pigs are always killed. One of the tasks performed y women is the breeding of pigs. According to Hylkema, a woman can only own a pig in an exceptional case, “though because a woman

From a social perspective, pigs are very significant. The number of pigs that an individual owns helps to determine his prestige. “An important man, a gain, owns many pigs. A person who does not own any or very few pigs cannot become a gain”, writes Peters. The pig is a medium of exchange: services, personal feats, debts and obligations towards each other are all paid with pigs or pigs meat. The pig also plays a key role in religious ceremonies for which one or more pigs are always killed. One of the tasks performed y women is the breeding of pigs. According to Hylkema, a woman can only own a pig in an exceptional case, “though because a woman  tends the pig she can assert some rights. It is her task to feed the pigs, to let them out in the morning and to bring them in again at night in the shelter, an extension along side the women’s entrance of the family dwelling”. Pigs are the personal property of men. However, according to Peters, “It does seem possible for women and children to own some pigs. In Anelekak village I was often shown pigs and given their owners’ name , including those of women and children”. Yet a couple of Peters’ informants denied that women and children could own pigs. Peters explains that “ According to them, the men gave their pigs to women and children to care for, who then regarded the pigs in their care, as their own”.

tends the pig she can assert some rights. It is her task to feed the pigs, to let them out in the morning and to bring them in again at night in the shelter, an extension along side the women’s entrance of the family dwelling”. Pigs are the personal property of men. However, according to Peters, “It does seem possible for women and children to own some pigs. In Anelekak village I was often shown pigs and given their owners’ name , including those of women and children”. Yet a couple of Peters’ informants denied that women and children could own pigs. Peters explains that “ According to them, the men gave their pigs to women and children to care for, who then regarded the pigs in their care, as their own”.

4. Pigs as payment for wife

“ At the Wisselmeren the price of women well as a pigs is expressed in terms of cowry shells. In other areas the correlation is even more straightforward and the price of women is directly defined in terms of the number of pigs,” says the ‘Father of Papuans’. Jan van Eechoud, in his book ’Vergeten Aarde (the Forgotten Earth).

“ At the Wisselmeren the price of women well as a pigs is expressed in terms of cowry shells. In other areas the correlation is even more straightforward and the price of women is directly defined in terms of the number of pigs,” says the ‘Father of Papuans’. Jan van Eechoud, in his book ’Vergeten Aarde (the Forgotten Earth).

In Papua Society, there are a lot of arguments about women; but even more about  pigs. Pigs are valuable and are even regarded as children.

pigs. Pigs are valuable and are even regarded as children.

“In the central Highlands, there is not much game and among Papuans in the bush only the piglets are caught and then bred for their meat. The care of these pigs is an important task. Quite often, you will see a woman with a baby piglet on one breast and her own one on the other.” (Jan van Eechoud, 1956)

5. Castrating pigs

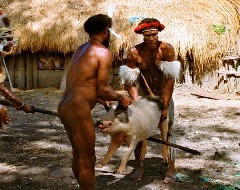

To encourage their growth, most of the boars are castrated (wam oupalygen wakanin). This operation is performed by men - and according to Hylkema – can also be done by women who know how to do this procedure. “ The pig is tied to a pole, with his head down”, writes Peters. “While one man holds the snout well shut, and others hang on tight to its legs, an expert removes the testicles using a sharp bamboo knife, after which the cuts are sewn together with fibers, and occasionally they put on some gray mud as well. A few of the boars are kept aside for breeding. It appears they want to avoid inbreeding in this way. A few times, I also saw other people from other villages come into Anelaka with a pig, to have it covered by one of the breeding boars from Takalek. If one had to pay for this, for example in the form of a piglet, I do not know.”

To encourage their growth, most of the boars are castrated (wam oupalygen wakanin). This operation is performed by men - and according to Hylkema – can also be done by women who know how to do this procedure. “ The pig is tied to a pole, with his head down”, writes Peters. “While one man holds the snout well shut, and others hang on tight to its legs, an expert removes the testicles using a sharp bamboo knife, after which the cuts are sewn together with fibers, and occasionally they put on some gray mud as well. A few of the boars are kept aside for breeding. It appears they want to avoid inbreeding in this way. A few times, I also saw other people from other villages come into Anelaka with a pig, to have it covered by one of the breeding boars from Takalek. If one had to pay for this, for example in the form of a piglet, I do not know.”

6. Killing the pigs

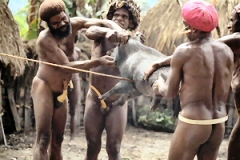

Killing a pig, is a task for a man. That a woman has some part to play, is expressed by the fact that she needs to position it and feed it with bataten, so that the man can take aim. Immediately after shooting it, the animal is cut into pieces to avoid the blood from cooling off and curdling.” (Hylkema). According to Peters, the customary killing and preparing of the pigs is done in the same way among the Dani. “ The pigs are shot in the heart with a bow an arrow, from close range at about 10 cm, after which they die very quickly, probably by suffocating. The tail and the ears are cut off and the hair is singed above an open fire. Cutting the meat into pieces is done as follows: Firstly, the skin on t

Killing a pig, is a task for a man. That a woman has some part to play, is expressed by the fact that she needs to position it and feed it with bataten, so that the man can take aim. Immediately after shooting it, the animal is cut into pieces to avoid the blood from cooling off and curdling.” (Hylkema). According to Peters, the customary killing and preparing of the pigs is done in the same way among the Dani. “ The pigs are shot in the heart with a bow an arrow, from close range at about 10 cm, after which they die very quickly, probably by suffocating. The tail and the ears are cut off and the hair is singed above an open fire. Cutting the meat into pieces is done as follows: Firstly, the skin on t he belly and the adhering layers of fat, muscles and jaw are sliced off in one go; then the membranes and muscles around the intestines are cut loose, and these are then lifted out, membranes and all. These are then cut open by other men after which the intestines are washed out by women and girls. The rest of the pig, thus all of the skin on its back with the adhering layers of fat, muscles and upper jaw, the legs and spinal column are left in one piece. This whole piece is called wam-oat. All of the internal organs, such as the heart, liver, lungs and so on and some of the meat are dried in the sun on sticks. The remainder goes straight into the cooking pit” (from Peters 1965).

he belly and the adhering layers of fat, muscles and jaw are sliced off in one go; then the membranes and muscles around the intestines are cut loose, and these are then lifted out, membranes and all. These are then cut open by other men after which the intestines are washed out by women and girls. The rest of the pig, thus all of the skin on its back with the adhering layers of fat, muscles and upper jaw, the legs and spinal column are left in one piece. This whole piece is called wam-oat. All of the internal organs, such as the heart, liver, lungs and so on and some of the meat are dried in the sun on sticks. The remainder goes straight into the cooking pit” (from Peters 1965).

7. Preparing the meat

The cross section of the rather shallow cooking pit usually varies from half a meter to a meter. “ Along the bottom of the pit, elongated bunches of grass are spread out and these stick a long way out over the side of the pit. On this grass come the stones, which have been well-heated; and on this they stack vegetables and potatoes, and then another layer of vegetables (usually the bataten leaves) or otherwise the leaves of a fern, then more stones; after which the whole thing is closed off with big pieces of skin from the back of the pig, followed by more vegetables with stones on top. The cooking pit is then sprinkled with water and the overlapping grass ends are subsequently used to completely cover the bataten, vegetables and meat. The food is left to smother for a good hour and a half, after which the pit is opened up again. Everything is well cooked by then” (from Peters 1965). Hylkema notes that the cooking pit is usually situated inside the fenced area of the men’s house. Peters points out that during ceremonies the cooking pit can be made on the village square and that the eating is also done there.

The cross section of the rather shallow cooking pit usually varies from half a meter to a meter. “ Along the bottom of the pit, elongated bunches of grass are spread out and these stick a long way out over the side of the pit. On this grass come the stones, which have been well-heated; and on this they stack vegetables and potatoes, and then another layer of vegetables (usually the bataten leaves) or otherwise the leaves of a fern, then more stones; after which the whole thing is closed off with big pieces of skin from the back of the pig, followed by more vegetables with stones on top. The cooking pit is then sprinkled with water and the overlapping grass ends are subsequently used to completely cover the bataten, vegetables and meat. The food is left to smother for a good hour and a half, after which the pit is opened up again. Everything is well cooked by then” (from Peters 1965). Hylkema notes that the cooking pit is usually situated inside the fenced area of the men’s house. Peters points out that during ceremonies the cooking pit can be made on the village square and that the eating is also done there.

8.Dividing the food

The big pieces of meat are divided up and everyone gets their particular portion. Hylkema indicates that among the Ngalum, the organs always go to the women and that pieces from the belly always go to the men. He states that the life force concentrates itself in the belly of the pig(kang-asum). “By eating a belly piece, mankind can taste and experience the essence of that which has been provided to him during his existence. His commonly threatened state of being is momentarily part of this life force and for an instant he experiences a state of absolute bliss”. The bataten and the vegetables are also distributed and the meat that is being dried on sticks, is eaten within the next few days. Normally, the Bataten are roasted in the ashes. When dividing the food, they make sure that everyone gets something to eat. Especially during big feasts, men walk around to ensure that every one is provided for”.

The big pieces of meat are divided up and everyone gets their particular portion. Hylkema indicates that among the Ngalum, the organs always go to the women and that pieces from the belly always go to the men. He states that the life force concentrates itself in the belly of the pig(kang-asum). “By eating a belly piece, mankind can taste and experience the essence of that which has been provided to him during his existence. His commonly threatened state of being is momentarily part of this life force and for an instant he experiences a state of absolute bliss”. The bataten and the vegetables are also distributed and the meat that is being dried on sticks, is eaten within the next few days. Normally, the Bataten are roasted in the ashes. When dividing the food, they make sure that everyone gets something to eat. Especially during big feasts, men walk around to ensure that every one is provided for”.

9.Links

- PACE- short film by Father Camps: Varkensfeest in Baliemvallei in 1974

- Short film by Age Postumus October, 2007: Papua people cooking pig

- Short film by Ed's Viewmaster: Varkensfeest 2004

- Short film by Adria Brocken: Varkensfeest tijdens trektocht Baliemvallei 2007

10.Sources

- S. Hylkema o.f.m., Mannen in het draagnet - mens- en wereldbeeld van de Ngalum (Sterrengebergte), ’s Gravenhage. 1974

- H.L. Peters, Enkele hoofdstukken uit het sociaal-religieuze leven van een Dani-groep,( Proefschrift), Venlo, 1965

- Jan van Eechoud, Vergeten aarde: Nieuw-Guinea, Amsterdam, De Boer, 1957

- Brongersma, L.D. en G.F.Venema, Het witte hart van Nieuw-Guinea. Met de Nederlandse expeditie naar het Sterrengebergte, Amsterdam: Scheltens & Giltay, 1960

- L. Pospíšil: The Kapauku Papuans of West New Guinea, in: George a Louise Spindler, Rinehart & Winston, New York, 1963

- L.F.B. Dubbeldam, ‘The devaluation of the Kapauku-cowrie as a factor of social disintegration’, In: New Guinea: The Central Highlands, American \Anthropologist, vol.66, no.4, Part 2, 1964

- Comments en advice: Nancy Jouwe