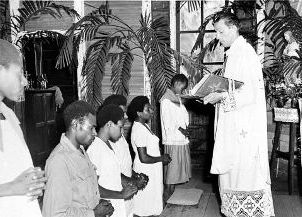

In 1939 the Dutch priest Jan Verscheuren witnessed a headhunting incident in kekaju village by the war-like tribe of the JEI people. He made notes which were then incorporated by Dr. Jan H.M.C. Boelaars in his book 'Nieuw Guinea uw mensen zijn wonderbaar' (New Guinea your people are amazing). Verscheuren described the killing and the rituals in great detail.

In 1939 the Dutch priest Jan Verscheuren witnessed a headhunting incident in kekaju village by the war-like tribe of the JEI people. He made notes which were then incorporated by Dr. Jan H.M.C. Boelaars in his book 'Nieuw Guinea uw mensen zijn wonderbaar' (New Guinea your people are amazing). Verscheuren described the killing and the rituals in great detail.

“The victim was hit on the back or killed by an arrow in order to avoid the head being crushed after which the head was cut off on the site of the killing”.

Jan Verscheuren died in a hospital in Jakarta on 28 July 1970.

Content

1. Preparing for headhunting

2. The Killing

3. Celebrating the skinning of the heads

4. Eating the meat

5. Background details on the Jei tribe

6. Links

7. Sources

1.Preparing for headhunting

In an obscure corner of the only cupboard of the small pastor’s home, I found some hand-written notes of Father Verscheuren, written at the time that he served at this post. They gave insight on the past of the Jei tribe of this territory.

In an obscure corner of the only cupboard of the small pastor’s home, I found some hand-written notes of Father Verscheuren, written at the time that he served at this post. They gave insight on the past of the Jei tribe of this territory.

“ Djilla, the commander of war around here, starts to talk about the fight coming up. He collects his men and says: ‘I am going to call the others as well’. He goes on his way and informs them of the day they are to gather at his village. When they arrive ,Djilla reveals where they will go and the date they will depart.

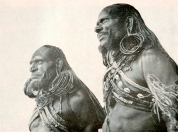

Every one adorns themselves, makes  kapero (decorative arrows), paints white chalk on their face and body and uses young coconut leaves to decorate their head. There is no singing. Then they are on their way, women and children come along too. Half way along the journey they make a stop and the commander and some of his men go out during the night to explore the area. They were going to the Kumbe and the Kanum people. Others that came with them are Kekaju, Seemb, Kedjau, Komadeo, Erambu and Birpa. Once he is satisfied with what he finds, he returns and signals this fact by jumping up and down several times, both feet in the air. He indicates the route to be taken and they leave for the village in silence, before dawn breaks.

kapero (decorative arrows), paints white chalk on their face and body and uses young coconut leaves to decorate their head. There is no singing. Then they are on their way, women and children come along too. Half way along the journey they make a stop and the commander and some of his men go out during the night to explore the area. They were going to the Kumbe and the Kanum people. Others that came with them are Kekaju, Seemb, Kedjau, Komadeo, Erambu and Birpa. Once he is satisfied with what he finds, he returns and signals this fact by jumping up and down several times, both feet in the air. He indicates the route to be taken and they leave for the village in silence, before dawn breaks.

2. The Killing

Near the village, the war party splits into three groups: Two start to surround the village, one from one side one from the other, while the commander stays behind until the other two are in position (which is communicated via messengers). They wait for sunrise, then with an air of secrecy the commander takes the lead, bow and arrow in hand and he shoots the first person he comes across, calls out his name after which the killing commences. They have brought their pugul. This club is derived from the Déma, God of the Marind-Anim. This story is as follows: Once they arrive at Moga, the children climbed into a tree to collect its fruits, when it suddenly grew very tall. One of the children jumped down and used the pugul to kill the tree. That is how they learnt of its use as a weapon.

Some of the warriors had taken their pugul along, others had not. The victim was hit on the back or killed by an arrow in order to avoid the head being crushed after which the head was cut off on site  (during the attack). Many were captured alive and decapitated while still alive, so that the body spun around, tottered off or filled itself up with sand and leaves. Arms and the lower parts of the leg were collected and sometimes the whole body was taken along. Children of the enemy were captured and subsequently brought up as their own. So if one came across a child, it was not beheaded. Young women were murdered, as was every adult in sight. Fathers taught their sons how to decapitate: He held on to the poor victim and let his son do the killing”.

(during the attack). Many were captured alive and decapitated while still alive, so that the body spun around, tottered off or filled itself up with sand and leaves. Arms and the lower parts of the leg were collected and sometimes the whole body was taken along. Children of the enemy were captured and subsequently brought up as their own. So if one came across a child, it was not beheaded. Young women were murdered, as was every adult in sight. Fathers taught their sons how to decapitate: He held on to the poor victim and let his son do the killing”.

3. Celebrating the skinning of the heads

Back in the village, hands and legs were eaten first, but they left the head hanging on a bamboo stick until the eyes bulged out and the head had started to rot. At this point, all the head hunters were called together and the top layer of skin and hair were rinsed off. The party to celebrate the skinning could start. When the remaining skin was being removed, the knife was placed on the head while they sang: Kwi oh wah wah oh.’ After having made a cut across the head, they sang: ‘Bene jürbür oh aoh bene jürbür oh eh’.

Back in the village, hands and legs were eaten first, but they left the head hanging on a bamboo stick until the eyes bulged out and the head had started to rot. At this point, all the head hunters were called together and the top layer of skin and hair were rinsed off. The party to celebrate the skinning could start. When the remaining skin was being removed, the knife was placed on the head while they sang: Kwi oh wah wah oh.’ After having made a cut across the head, they sang: ‘Bene jürbür oh aoh bene jürbür oh eh’.

Everyone got up at this point: one grabbed the skinned head, another skin, a third the knife. Everything was held up high towards the sun and the üd tjerimetje (the man wearing the knife) solemnly called to the sun: ‘Mir ah, aripe iripe nepi’ (sun, this head, I now cut). He spoke these words in the hope of catching yet another person the next time around. De üd tjerimetje started to cut at the nose. At the same time, all those present called out: ‘Tjürowih ah, tjürowih ah’ (receive,

Everyone got up at this point: one grabbed the skinned head, another skin, a third the knife. Everything was held up high towards the sun and the üd tjerimetje (the man wearing the knife) solemnly called to the sun: ‘Mir ah, aripe iripe nepi’ (sun, this head, I now cut). He spoke these words in the hope of catching yet another person the next time around. De üd tjerimetje started to cut at the nose. At the same time, all those present called out: ‘Tjürowih ah, tjürowih ah’ (receive,

receive) and all of them started to bend quietly at the knees, until they were down on their knees”.

4. Eating the meat

The meat and the brains were collected up most carefully and made into a garmu: a loaf of sago, meat and bamboo thorns, which had been pounded into pulp beforehand. Especially young people had to eat from this. The loaf was divided and then they said:’ The next time you will catch as the thorns of the bamboo catch men’ Even the skin, thrown aside earlier on, was eaten. Once the meat was off the skulls, these were dried above the fire until they turned white.

The meat and the brains were collected up most carefully and made into a garmu: a loaf of sago, meat and bamboo thorns, which had been pounded into pulp beforehand. Especially young people had to eat from this. The loaf was divided and then they said:’ The next time you will catch as the thorns of the bamboo catch men’ Even the skin, thrown aside earlier on, was eaten. Once the meat was off the skulls, these were dried above the fire until they turned white.

The jaw was connected with three pieces of rope: two on either end and one in the middle. A bamboo stick, hung down from a tree, was split and the heads were attached to these in a bunch. The bones of the arms and legs were made into a ladder using two bamboo sticks. The skulls were hung from the nose. The knuckle bones of the hands and feet were strung together and the elderly wore them around their neck. The name, when this was not known, was requested of its victim and this was later given to their own child. This was explained as follows: The father wants to ensure that his heroic action is remembered.

The jaw was connected with three pieces of rope: two on either end and one in the middle. A bamboo stick, hung down from a tree, was split and the heads were attached to these in a bunch. The bones of the arms and legs were made into a ladder using two bamboo sticks. The skulls were hung from the nose. The knuckle bones of the hands and feet were strung together and the elderly wore them around their neck. The name, when this was not known, was requested of its victim and this was later given to their own child. This was explained as follows: The father wants to ensure that his heroic action is remembered.

5. Some background details on the Jei tribe

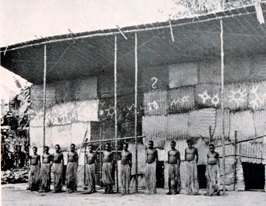

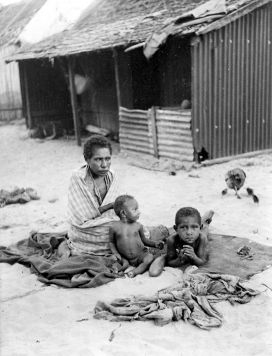

The size of this tribe in July 1948: 1017 souls, divided across 9 kampongs, which is about 100 people per kampong

Bupuls: 200. Originally, the Jei-Anim had a higher material culture than the Marin-Anim. Based on the study results from the boarding school in Merauke, the former learnt more easily than the latter. Verscheuren told me about the exceptional musical ability of these people.

6. Links

Refer to: Head hunters of the South Coast

7. Sources

Overgenomen uit:

- Nieuw Guinea uw mensen zijn wonderbaar. Het leven der Papua’s in Zuid Nieuw Guinea, Dr. J. Boelaars, Bussum 1953.

Verder:

- Snellen om namen. De Marind Anim van Nieuw-Guinea door de ogen van de missionarissen van het Heilige Hart 1905-1925, Raymond Corbey, Leiden 2007

- Jan Verschueren's Description of Yéi-nan Culture (Extracted from the Posthumous Papers). Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land en Volkenkunde 99, J.van Baal, The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1982.