An elongated stretch of land along the south-west coast of New Guinea (Papua) is the home ground of the Kamoro. Adapting to the shifting tides, this semi-nomadic tribes live in various places along the coast from FakFak to Merauke. But as is the case every where, the modern world has infiltrated their lives. The American mining company Freeport which operates in this area, has led to the Kamoro becoming a minority within their own territory. Logging companies have also moved in and large pieces of land were confiscated for Indonesian migrants without informing the locals or obtaining their approval.Many of the Kamoro have lost valuable knowledge of their culture and traditional lifestyle because for quite a long time it was forbidden to engage in their religious activities and certain elements of their traditional lifestyle were being actively discouraged. Kamoro Culture was regarded as an obstacle by both the Protestant Church and the authorities under Dutch rule and again by the Indonesian authorities in later years. However, in recent years many aspects of the traditional culture are being reintroduced and this development is being supported by both church and state. The arrival of the Kamoro Art Festival has in fact led to a renaissance of indigenous culture.

An elongated stretch of land along the south-west coast of New Guinea (Papua) is the home ground of the Kamoro. Adapting to the shifting tides, this semi-nomadic tribes live in various places along the coast from FakFak to Merauke. But as is the case every where, the modern world has infiltrated their lives. The American mining company Freeport which operates in this area, has led to the Kamoro becoming a minority within their own territory. Logging companies have also moved in and large pieces of land were confiscated for Indonesian migrants without informing the locals or obtaining their approval.Many of the Kamoro have lost valuable knowledge of their culture and traditional lifestyle because for quite a long time it was forbidden to engage in their religious activities and certain elements of their traditional lifestyle were being actively discouraged. Kamoro Culture was regarded as an obstacle by both the Protestant Church and the authorities under Dutch rule and again by the Indonesian authorities in later years. However, in recent years many aspects of the traditional culture are being reintroduced and this development is being supported by both church and state. The arrival of the Kamoro Art Festival has in fact led to a renaissance of indigenous culture.

Content:

1. Villages along rivers and coastal areas

2. Ritual and Woodcarvings

3. Kàware: canoe festival

4. Mbitoro: Spirit Poles

5. History of Mimika area

6. Stapel foods: sago and fish

7. Kamoro Art Festival

8. Links

9. Sources

1. Villages along the rivers and coastal areas

The Kamoro live in the West, Central and East Mimika districts situated in the coastal zone which runs from FakFak to Merauke along the Afura Sea which is about 300 km long. It is estimated that about 15.000 to 18.000 people live in this area. About 40 villages, with a 100 to 500 inhabitants each, are situated either along the river or on the sea front.

Most of the Kamoro move from one place to the next in their traditional prauw (wooden canoe made from a tree trunk).

Their territory borders on that of the Amungme in the west and that of the Sempat and Asmat in the east. Very few people live in the coastal area to the east of the Otokwa River and it remains sparsely populated right up to the Asmat territory along Flamingo Bay. In West and Central Mimika the villages are on a built up beach area and are surrounded by water at high tide. Behind the sea wall is a swampy bushland, navigable along the meandering waterways that run though it.

In East Mimika the villages are more inland along the banks of the Kamoro, Wania inawka, Omawka and Otokwa Rivers. The Kamoro language belongs to the Kamoro-Asmat Language group. The Kamoro people are more generally known by their tribal names and these are as follows: Kamora, Mimika Lakahia, Nagramadu, Umari, Mulkamuga, Neferipi, Nefaripi, Maswena, Nafa, Kaokonau, and Umar. The three main dialects of the Kamoro language are: Tarya, Yamur and Nanesa.

2. Rituals and Woodcarving

In the villages situated along the upper reaches of the rivers , the most important festival is Emakame ( literally : house of bones). The Kamoro build a special festival house for storing the bones of their ancestors. The bones of the recently deceased are excavated and are kept in the homes of tribesmen in preparation for the festival. The central themes of this festival are: life arising from death, renewal of life and the origin of life itself. These themes are based on a creation myth. In East mimika, the local version of this festival, is called Kiawa.

Traditionally, woodcarving plays an important role in the rituals that belong to this festival. For the Emakame ritual, shields or Yamate are used, the carving of which symbolises life and death, and the way life originates from death. Jan Pouwer, who had undertaken an anthropological research project of the Kamoro in August 1951 wrote the following : “Essentially, each Yamate ancestral figure represents a recently deceased fellow villager”

During the Emakame ritual, the women play an important role because they are the ‘carriers’ of new life. One of the goals of the festival is to enhance fertility. During the festivities women consume a particular substance which is assumed to facilitate conception.

3. Kàware: the tree-canoe festival

The Kàware Festival celebrates new life after death. This festival is associated with the sea, the beach and the coast. The Kàware ritual is dedicated to the spiritual aspect of male fertility and passing on of male skills. Thus the men are trained to be wood cavers and at this time new canoes are carved out of a specially felled trees selected for the ceremony. These canoes are decorated with special ornaments placed on the prow and with festively carved paddles, which have been cut from a hard wood. Because of the canoe-making aspect of the festival, it is also known as the tree-canoe festival.

The Kàware Festival celebrates new life after death. This festival is associated with the sea, the beach and the coast. The Kàware ritual is dedicated to the spiritual aspect of male fertility and passing on of male skills. Thus the men are trained to be wood cavers and at this time new canoes are carved out of a specially felled trees selected for the ceremony. These canoes are decorated with special ornaments placed on the prow and with festively carved paddles, which have been cut from a hard wood. Because of the canoe-making aspect of the festival, it is also known as the tree-canoe festival.

At the festival, a Mamokoro or Mbiikao mask, made out of rope, is warn. It has a high pointy head with a long beak which is attached to a skeleton of rattan and it has a sheath around it made from sago leaf fibres. These masks are found in the central and eastern parts of the Mimika area. The traditional powers and special meaning attributed to these masks have not lost their significance and today they still form a crucial link between the various Kamoro customs which they adhere to. There are of course certain ‘adaptations’ to account for ‘modern’ life. Increasingly, these masks are sold to tourists and as such they have become a source of income. The Kamoro are also expected to consider the school, work- and religious calendar and they have to announce their plans to the authorities in plenty of time.

4. Mbitoro: Spirit Poles

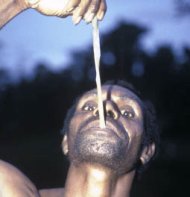

Mbitoro, the ceremonial spirit pole made out of a wild Nutmeg tree, belongs to the most spectacular of  wood carvings. They vary in height from miniatures no more than 40 cm in length to poles, at least 4 metres high. These can be compared to the Asmat Bisj Poles which have a similar shape and function. In both cases, the carving is used in rituals and they symbolises those recently passed away. A Mbitoro pole has one, two or at the most three carved male figures on it, whose bodies are interwoven, as well as an okemere, a flag-shaped protrusion at the top of the pole. The latter is made from the roots of the mangrove tree. Besides the tribute being made to the deceased, the Mbitoro is also of central importance to an initiation ritual, used in mythic times. Nowadays, this ritual is performed more and more but without the nose piercing element, using a stick which can be as much as four metres long.

wood carvings. They vary in height from miniatures no more than 40 cm in length to poles, at least 4 metres high. These can be compared to the Asmat Bisj Poles which have a similar shape and function. In both cases, the carving is used in rituals and they symbolises those recently passed away. A Mbitoro pole has one, two or at the most three carved male figures on it, whose bodies are interwoven, as well as an okemere, a flag-shaped protrusion at the top of the pole. The latter is made from the roots of the mangrove tree. Besides the tribute being made to the deceased, the Mbitoro is also of central importance to an initiation ritual, used in mythic times. Nowadays, this ritual is performed more and more but without the nose piercing element, using a stick which can be as much as four metres long.

In Kamoro culture a drum is used to invoke spirits, forefathers and other beings. The elongated drums are shaped by burning away the inside of a tree trunk. This is an intricate process that requires skill to make the sides of the drum thin enough to produce the right vibrations. The top part of the drum is covered with the skin of a reptile (usually the Mangrove Monitor Lizard or Varanus Salvador). In the past mixture of lime from burnt shells and human blood from a sister or the husband of a daughter had to be used to adhere the skin to the wooden frame. But these days anyone’s blood will do. To allow the lizard skin to stretch tight and get the right pitch, it is kept close to the fire.

5. History of Mimika area

When the first Europeans arrived in the area at the beginning of the 17th century, the Kamora had already been in contact with Molukkan, Chinese and Malaysian traders. They traded the medicinal bark of the Massooi Tree and slaves.

In 1623, when the Dutch VOC Captain Jan Carstenz sailed along the coast with his two ships the Terra and the Arnhem, he actually saw mountains covered in snow. In Europe they barely believed his rapport because of the hot tropical climate.

Some years later, during a VOC expedition in 1636, Captain Gerrit Pool was murdered by Kamoro from the East of Mimika However in 1828 the participants of the Dutch Triton Expedition managed to spend a peaceful 11 days in the Kamoro area. They intended to annex the area to make it a part of the Dutch East Indies before the English could do so. Their attempt failed and administrational control did not occur until the beginning of the 20th century. At this time the Dutch Military undertook a number of expeditions in Papua. During one of these, under the leadership of Captain A.J. Gooszen (1907–1915), Kamoro Art work was collected for the very first time. About half of the collection at the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden dates back to this particular expedition. In 1910-11 and 1912 the first westerners visited the hinterland. They were the members of two British expeditions, the British Ornithologist Union and the Royal Geographical Society. They attempted to reach the tops of the Carstensz Mountains via the Mimika region and they got a friendly reception form the Kamoro when they passed through. Then in 1926 , the first Dutch Administration post was set up at Koakonao by the mouth of the Mimika River. This administrative post included 4 villages and had more than 500 inhabitants. In 1927 a mission post was also set up by the Roman Catholics. The area was under Dutch administration from 1926 to 1963 and practically every one was baptised during this period. At that time the Dutch police force used modern weapons when Asmat tribes raided Kamoro villages for iron resources that they had.

In World War II during the Japanese occupation of about 1000 soldiers( 1942-1945), the Kamoro did not offer the enemy any assistance but neither did they sabotage them.

6. Stapel foods: sago and fish

In the past food production was dependent on a cycle of smaller and larger festivals. Kamoro houses are situated near very rich mangrove swamps. In 2008 about 70 percent of the Kamoro still lived mainly on sago and fish. Apart from fishing, they also hunt in the forest for wild pigs , cassowary large flightless bird) and possums. Women collect crabs and shellfish which live in the swampy areas between the coast and the river upstream. They also grow tobacco (kapaki) and a variety of crops such as sugar cane(monè) and banana (kaw). Attempts by the misionary to make them into farmers failed. Further attempts by the Dutch and Indonesian authorities did not succeed either. The basic staple sago is easily available, which is why the Kamoro do not see the point of changing. They regularly move up and  down between their fishing grounds along the coast and their gardens inland at the kapiri kamé (temporary homes made of pandanus leaves). The sago palms grow in their gardens in the bush. When these are cut , the bark is removed with a wedge. The tree trunk is not cut into pieces but is made into a gutter when they beat the core into a fine sago flour with a apènata-maare (a conical shaped sago beater). The sago is then kneaded with water and squeezed through a sieve placed in a section of the gutter. The sago is stored and transported in a tumang (container), 80 to 90 inches long. Some that were of the sago palms felled, are left to rot. The rotting process causes the growth of sago grubs or kò. The larvae of the sagobokter is a favourite Kamoro delicacy. Another delicacy is tambelo, a type of mollusc found in cut down mangrove trees. These delicacies are either eaten raw or roasted on the fire.

down between their fishing grounds along the coast and their gardens inland at the kapiri kamé (temporary homes made of pandanus leaves). The sago palms grow in their gardens in the bush. When these are cut , the bark is removed with a wedge. The tree trunk is not cut into pieces but is made into a gutter when they beat the core into a fine sago flour with a apènata-maare (a conical shaped sago beater). The sago is then kneaded with water and squeezed through a sieve placed in a section of the gutter. The sago is stored and transported in a tumang (container), 80 to 90 inches long. Some that were of the sago palms felled, are left to rot. The rotting process causes the growth of sago grubs or kò. The larvae of the sagobokter is a favourite Kamoro delicacy. Another delicacy is tambelo, a type of mollusc found in cut down mangrove trees. These delicacies are either eaten raw or roasted on the fire.

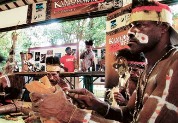

7. Kamoro Art Festival

In 1967, Freeport Mining received permission from the Indonesian government to excavate gold and copper in this area. Lemasko, an organisation of Kamoro tribes, did not sign a land right agreement with Freeport until 2000. The arrival of Freeport had far reaching consequences for the natural environment and the Kamoro way of life as they were forced to shift their villages. On the up-side, Freeport sponsors the annual Kamoro Art Festival or Kamoro Kakuru which has been held in the village of Pigapu since 1998.  The Hungarian-American Photographer and Anthropologist Karl Muller, who was concerned about the Welfare of the Kamoro, became a special advisor to Freeport. He also started going around the villages to buy wooden sculptures. The main objective of the art festival is to retain Kamoro heritage. The Kamoro Art Festival came about because of the annual Asmat art auction which had been set up by Bishop Alphonse Sowada. He had also founded the Asmat museum at Agats in 1973. According to Muller the Asmat have retained their traditional lifestyle more than the Kamoro have. These two tribal cultures use the same symbols when they do their carving but the Kamoro sculptures are smoother and more elegant.

The Hungarian-American Photographer and Anthropologist Karl Muller, who was concerned about the Welfare of the Kamoro, became a special advisor to Freeport. He also started going around the villages to buy wooden sculptures. The main objective of the art festival is to retain Kamoro heritage. The Kamoro Art Festival came about because of the annual Asmat art auction which had been set up by Bishop Alphonse Sowada. He had also founded the Asmat museum at Agats in 1973. According to Muller the Asmat have retained their traditional lifestyle more than the Kamoro have. These two tribal cultures use the same symbols when they do their carving but the Kamoro sculptures are smoother and more elegant.

The Kamoro Art Festival has become a source of income for sculptors and women weavers who make bags from local grasses. Dancing performances, cooking demonstrations and canoe races are also organized for the festival. At the festival in 2005, 11 million Rupiah was paid for one particular sculpture, the biggest sum ever.

8. Links:

– 'Articles and notes' about Kamoro by Kal Muller 0n Papuaweb, updated 29 March 2004.

– Kamoro Art Festival uit 2003 includes carving, dance performances and canoe racing in Pigapu.

– From research on Kamoro food gathering: Kamorokokosnootoogst en visactiviteiten in Mimika Regency by pwarr3n, (February 2004)

– Jakarta Globe, 22 oktober 2009: Kal Muller over kunst en trots van de Kamoro.

- The Kamoro. ‘The coastal people of West Papua’ website article by Kal Muller on indahnesia.com.

- Maskers uit het Mimika-gebied (Nieuw-Guinea), Museum for Ethnography in Leiden.

9. Sources:

– J. Akkermans, From Missie van Mimika. Annalen van Onze Lieve Vrouw van het Heilige Hart. 56: 149-150, 1938.

– J. Coenen OFM, Enkele facetten van de geestelijke cultuur van de Mimika. Omawka: OFM. Unpublished typescript, 1963, held at the National Museum of Ethnography in Leiden.

– Todd Harple, Controlling the dragon: An ethno-historical analysis of social engagement among the Kamoro of South-West New Guinea (Indonesian Papua/Irian Jaya). PhD thesis, Australian National University, Canberra, 2000.

– Bruce M. Knauft, South coast New Guinea cultures: History, comparison, dialectic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

– Simon Kooijman, Art, art objects and ritual in the Mimika culture in Mededelingen van het Rijksmuseum van Volkenkunde, Leiden 24. Leiden: Brill,1984.

– Kal Muller, Pride and Prejudice: the Kamoro Culture of South Irian. Garuda4(10):24-25, 1996.

- David Pickell, Kamoro: Between the tides in Irian Jaya. With photographs by Kal Muller. Jakarta: Aopao Productions, 2001.

– Jan Pouwer, Enkele aspecten van de Mimika-cultuur (Nederlands Zuidwest Nieuw Guinea). PhD thesis, University of Leiden, Leiden. Den Haag: Staatsdrukkerij, 1955.

– Jan Pouwer, Rechten op de grond in Mimika. Adatrechtbundel 45:569-582. Den Haag: Nijhoff. 1955, republished 1970.

– Jan Pouwer, A masquerade in Mimika. Antiquity and Survival 1(5):373-386, 1956.

– Jan Pouwer, Mimika land tenure. New Guinea Research Bulletin 38:24-33. Canberra: Australian National University, 1970.

– Jan Pouwer, Structural history: A New Guinea case study. In: W.E.A. van Beek and J.H. Scherer (eds), Explorations in the anthropology of religion: Essays in honour of Jan van Baal (pp. 80-111). Verhandelingen 74. The Hague: Nijhoff, 1975.

– Pouwer, Gender in Mimika: Its articulation, dialectic and its connection with ideology. Paper presented at the International New Guinea Workshop, University of Nijmegen, Nijmegen, February 24-26, 1987.

– Pouwer, Mimika. In:Terence E. Hays (ed.), Encyclopedia of world cultures, Volume 2: Oceania (p. 209). Boston: Hall, 1991.

– Jan Pouwer and Gertrudis A.M. Offenberg, (eds). Amoko - In the beginning: Myths and legends of the Asmat and Mimika Papuans. Adelaide: Crawford House Publishing, 2002 (tonycraw@bigpond.net.au). Only available from the bookstore 'De Verre Volken' in the National Museum of Ethnology at Leiden, Netherlands (info@ethnographicartbooks.com), 2002.

– Dirk Smidt, Kamoro art: Tradition and innovation in a New Guinea culture. Amsterdam: KIT Publishers, 2003.

– UnCen-ANU Baseline Studies Project. Kamoro Baseline Study final report. UABS Report 7. Jayapura and Canberra: Universitas Cenderawasih and Australian National University,1998.

– Pauline van der Zee, Art as contact with the ancestors. The visual arts of the Kamoro and Asmat of Western Papua. KIT Publishers, Amsterdam, 2009.

– Advice and comments: Pauline van der Zee, lecturer Ethnographic Collection at the University of Gent in Belgium.