Before World War II, former Dutch New Guinea, now the Indonesian provinces of Papua and West Papua, was regarded in the media as still being part of the so-called Stone Age. Irrespective of it being a useful concept, there were at least two reasons to take a more tempered view. Firstly, because iron implements were introduced shortly after contact with the first European ship in the area.

Before World War II, former Dutch New Guinea, now the Indonesian provinces of Papua and West Papua, was regarded in the media as still being part of the so-called Stone Age. Irrespective of it being a useful concept, there were at least two reasons to take a more tempered view. Firstly, because iron implements were introduced shortly after contact with the first European ship in the area.

Secondly, because in North West Papua traditional iron tools  and weapons were being made by local blacksmiths themselves long before Europeans arrived on the scene. Making iron objects has been an important aspect of the culture of the inhabitants of coastal areas and islands of North West Papua. Groups of blacksmiths who were in contact with the supernatural world developed on the island of Biak and in the Dorebaai area- the north western part of the Geelvinkbaai-. However, this particular area of New Guinea was the only one in which iron weapons were being made.

and weapons were being made by local blacksmiths themselves long before Europeans arrived on the scene. Making iron objects has been an important aspect of the culture of the inhabitants of coastal areas and islands of North West Papua. Groups of blacksmiths who were in contact with the supernatural world developed on the island of Biak and in the Dorebaai area- the north western part of the Geelvinkbaai-. However, this particular area of New Guinea was the only one in which iron weapons were being made.

Content

1. The arrival of iron

2. Where iron came from

3. The art of forging iron

4. The use of the bellows

5. Blacksmiths from Biak travel far

6. The significance of iron for Papua culture

7. Links

8. Sources

1.The arrival of iron

The art of working iron probably reached New Guinea in the middle of the 19th century after contact with the sultanate of Tidore where Islam was introduced between 1400and 1450. The bellows fanned by a charcoal fire probably dates back to this period as well. The contact with Islam also explains the taboo on eating pork among the blacksmiths of Papua. Trade with the inhabitants of the Moluccas ensured Papua a supply of iron. The first written evidence of importing iron comes from the middle of the 18th century. Documentation from the 19th century reveals that merchants from Tidore came to the Geelvinkbaai(bay) with iron machetes, axes, knives and rods. Such iron implements were traded for turtle shells, birds of Paradise, sea cucumbers and Tapa cloth made from bark. The introduction of iron tools saved an enormous amount of time for the men.

2. Where iron came from

It is thought that the imported machetes were made by Timorese blacksmiths from old iron that originally came from China. As far as we know, the Tidore and Moluccas did not make any knives and axes themselves. The knives, axes and iron rods, which were imported into Papua during the 19th century, actually came from Europe. Papuan blacksmiths forged the iron bars into spear heads and harpoons.

It is thought that the imported machetes were made by Timorese blacksmiths from old iron that originally came from China. As far as we know, the Tidore and Moluccas did not make any knives and axes themselves. The knives, axes and iron rods, which were imported into Papua during the 19th century, actually came from Europe. Papuan blacksmiths forged the iron bars into spear heads and harpoons. The imported machete were also worked on by the Papuan blacksmith to make them harder and more durable. At the beginning of the 20th century, the price that was being paid for such machetes on the island of Biak was twice the amount being paid for the ones brought in by Chinese merchants. Shortly after World War II, the blacksmiths from Biak used old iron from American army material. For example, one came across machetes made from metal suspension coils of old trucks.

The imported machete were also worked on by the Papuan blacksmith to make them harder and more durable. At the beginning of the 20th century, the price that was being paid for such machetes on the island of Biak was twice the amount being paid for the ones brought in by Chinese merchants. Shortly after World War II, the blacksmiths from Biak used old iron from American army material. For example, one came across machetes made from metal suspension coils of old trucks.

3. The art of forging iron

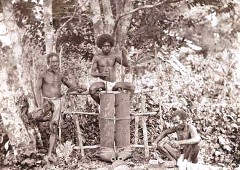

Forging iron is associated with special secrets. This is especially true for the island of Biak and the area around Dorebaai, where groups of blacksmiths developed special contact with the supernatural. A man who wants to learn the art of forging iron has to be initiated. The training consists of learning technical skills, specific magical procedures and a number of magic spells. The apprentice blacksmith may not wash himself for a certain period of time and has to abstain from food and sexual intimacy. At the start of this training, the apprentice makes simple objects such as rod-shaped iron points with barbs on them for fishing spears. At the end

Forging iron is associated with special secrets. This is especially true for the island of Biak and the area around Dorebaai, where groups of blacksmiths developed special contact with the supernatural. A man who wants to learn the art of forging iron has to be initiated. The training consists of learning technical skills, specific magical procedures and a number of magic spells. The apprentice blacksmith may not wash himself for a certain period of time and has to abstain from food and sexual intimacy. At the start of this training, the apprentice makes simple objects such as rod-shaped iron points with barbs on them for fishing spears. At the end  of his apprenticeship, he has to make a machete as a test of his aptitude. Only when he has participated in a so called Hong-trip, during which he uses the recently made weapons for headhunting, can he be regarded as a full-blown blacksmith (see links to headhunting).

of his apprenticeship, he has to make a machete as a test of his aptitude. Only when he has participated in a so called Hong-trip, during which he uses the recently made weapons for headhunting, can he be regarded as a full-blown blacksmith (see links to headhunting).

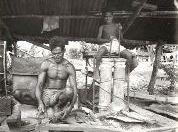

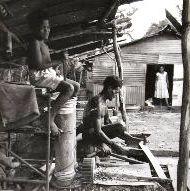

Blacksmiths in North West Papua manufacture multiple spearheads for fishing harpoons, machetes, a range of smaller knives and iron bracelets. They make use of an anvil, a hammer and bellows for forging the fire.

4. The use of bellows

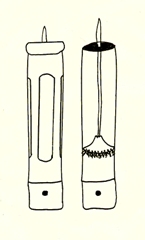

Bellows ,definitely in use by 1850, but probably before, have undergone little to no adaptation since they were introduced. They consist of two bamboo cylinders of even length and diameter. These are arranged in up-right position, one next to the other. The cylinders are open at the top but they have been fitted with wooden caps at the bottom. There is a small whole along the side at the bottom of

Bellows ,definitely in use by 1850, but probably before, have undergone little to no adaptation since they were introduced. They consist of two bamboo cylinders of even length and diameter. These are arranged in up-right position, one next to the other. The cylinders are open at the top but they have been fitted with wooden caps at the bottom. There is a small whole along the side at the bottom of  each cylinder for the air to escape. Air is produced by means of a pumping device or “ pumping rod”, one for each cylinder. At the bottom of each rod a wooden cone has been attached with rope made of bamboo fibre. To make the cylinder as airtight as possible, feathers have been fixed along the outside of each cone. Perched on a scaffold behind the cylinders, the apprentice pumps the necessary amount of air out, alternating between his right and his left hand to keep the bellows going.

each cylinder for the air to escape. Air is produced by means of a pumping device or “ pumping rod”, one for each cylinder. At the bottom of each rod a wooden cone has been attached with rope made of bamboo fibre. To make the cylinder as airtight as possible, feathers have been fixed along the outside of each cone. Perched on a scaffold behind the cylinders, the apprentice pumps the necessary amount of air out, alternating between his right and his left hand to keep the bellows going.

5. Blacksmiths from Biak travel far

The blacksmiths from Biak become travelling merchants. With their prauw (type of canoe), they are able to travel great distances. They roam an area which extends as far as Timor to the west and the border with Papua New Guinea to the east.

The blacksmiths from Biak become travelling merchants. With their prauw (type of canoe), they are able to travel great distances. They roam an area which extends as far as Timor to the west and the border with Papua New Guinea to the east.

6.The significance of iron for Papua culture

The production of iron objects is not only significant for the material aspects of culture but it also influences social organisation, religion and mythology. Thus iron and weapons made from iron have a role in creation myths in which death and war are important themes. Taboos are put in place during ceremonies regarding the use of iron objects for certain individuals, pregnant women for example. Machetes have ceremonial uses and form part of the dowry. Myths describe the origin of iron as a miracle and it is regarded as supernatural. For this reason fire, through which iron is forged, has a sacred aspect to it. This is clear form the Biak word for iron: ‘romawa foria’= ‘child of the fire’. The blacksmiths of Biak were highly thought off because of their power over the iron, their technical skills, their secret magical knowledge, and their special contact with the supernatural world.

The production of iron objects is not only significant for the material aspects of culture but it also influences social organisation, religion and mythology. Thus iron and weapons made from iron have a role in creation myths in which death and war are important themes. Taboos are put in place during ceremonies regarding the use of iron objects for certain individuals, pregnant women for example. Machetes have ceremonial uses and form part of the dowry. Myths describe the origin of iron as a miracle and it is regarded as supernatural. For this reason fire, through which iron is forged, has a sacred aspect to it. This is clear form the Biak word for iron: ‘romawa foria’= ‘child of the fire’. The blacksmiths of Biak were highly thought off because of their power over the iron, their technical skills, their secret magical knowledge, and their special contact with the supernatural world.

7. Links:

- Explanation by Dirk Vlasblom in an article about Cargo cults “ Papua’s in de ban van geld en goed”

- Article about a machete on museumkennis.nl

- Article about the iron arrow head on museumkennis.nl

- Article on iron spear head for a fishing spear on museumkennis.nl

- Theme page on PACE website about headhunting on the south coast.

8. Sources:

- F.C. Kamma, en S. Kooijman, ‘Romawa Forja, Child of the Fire’: Iron working and the role of iron in West New Guinea (West Irian).

- Advice from Frits Cowan, former curator of the Tropeninstituut in Amsterdam.