>> Heritage as an expression of identity

Desire for an actual formulation of a collective identity and a sense of belonging is increasing within the Papua Community. Developing and strengthening self-esteem within Papua Communities in diaspora happens largely through various forms of heritage. Papuans themselves focus mainly on music, dance, imagery and history as important expressions of their own heritage. Oral History, the recording of personal life stories and histories of migration, is increasingly considered to be important because the first generation of Papuans in the Netherlands is now between 65 and 85 years of age. However, the average life expectancy of Papuans in the Netherlands is lower than the national average, most die before reaching 65-70. We need to record their stories before it is too late. In 2009 PACE conducted an Oral History Project among first generation Papuans living in the Netherlands (Refer to Pigsalon report for details on this project).

Desire for an actual formulation of a collective identity and a sense of belonging is increasing within the Papua Community. Developing and strengthening self-esteem within Papua Communities in diaspora happens largely through various forms of heritage. Papuans themselves focus mainly on music, dance, imagery and history as important expressions of their own heritage. Oral History, the recording of personal life stories and histories of migration, is increasingly considered to be important because the first generation of Papuans in the Netherlands is now between 65 and 85 years of age. However, the average life expectancy of Papuans in the Netherlands is lower than the national average, most die before reaching 65-70. We need to record their stories before it is too late. In 2009 PACE conducted an Oral History Project among first generation Papuans living in the Netherlands (Refer to Pigsalon report for details on this project).

Colonial past: Papua heritage as a source of knowledge

The average Dutchman does not know that there are Papuans in the Netherlands.

The average Dutchman does not know that there are Papuans in the Netherlands.

Moreover, many Dutch people have a complex relationship with their colonial past, especially concerning their attitude towards Papua (former Dutch New Guinea): there is a sense of shame about the course of colonisation. This shame towards Papuans is caused, among other things, by the fact that the Dutch had promised them independence.

In former Dutch New Guinea efforts were made to establish infrastructure and economical development. A political framework and a Papuan parliamentary body (New Guinea Council) were created as well.

Various national symbols were designed (the Morning Star flag, the national coat of arms, an anthem). The official question of the Dutch Government to Papuans was on which date they wished to become independent. While these motions were taking place internally at the time, international politics decided otherwise. Papua was transferred to Indonesia in May 1963 and after a public consultation in 1969 it became a province of Indonesia. The Dutch who immediately had to leave New Guinea in mid-1962 did so full of guilt towards the Papuans.

Historical interpretation

The general feeling was that they abandoned the Papuans. By unlocking the still largely unknown stories and histories, a more complex historical interpretation and a growing awareness of the existence of a shared history emerges.

The general feeling was that they abandoned the Papuans. By unlocking the still largely unknown stories and histories, a more complex historical interpretation and a growing awareness of the existence of a shared history emerges.

Despite the recently installed canon in which Papuans are mentioned by name, very little substantive information about the Dutch colonization of what is now called West Papua and other former colonies is transferred within the Dutch educational system.

Recent research shows that among youth as well as adults in the Netherlands, awareness of this colonial history is limited. In fact, Dutch society lags behind in knowledge, compared to neighbouring countries.

Multicultural debate

Papua Heritage within the Netherlands (as well as in Papua itself) has a significate function for maintaining cultural identity. We need knowledge of the past to understand the present and shape the future. The colonization of New Guinea and the Papuan history of migration to the Netherlands are very concrete manifestations of a relatively unknown part of Dutch History. Historical interpretation is crucial if we are to better understand the Netherlands today and if we want to make progress on the current multicultural debate in which groups are regularly unfairly stereotyped. This hardens Dutch attitudes. Cultural heritage information on minority groups such as the Papuans can counteract this trend.

Dynamics of heritage: different meanings

PACE advocates a dynamic view of heritage: heritage is placed in context and time. The result is that heritage can have different meanings to different people but may also have different meanings in different periods. An example is the appreciation of Papua artefacts.

PACE advocates a dynamic view of heritage: heritage is placed in context and time. The result is that heritage can have different meanings to different people but may also have different meanings in different periods. An example is the appreciation of Papua artefacts.

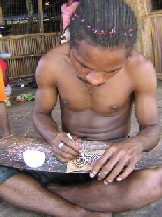

Makers often produce artefacts as utensils for daily life, or as objects that have a function in certain rituals and festivals after which they are returned to nature. Bisj poles are a good example of this. The Papuans, in all their diversity, made their artefacts not necessarily for the long term.

Meanwhile, artefacts are also made as items for sale in the tourist industry since a market has been created for them. Shipping artefacts abroad by Westerners, then and now, led to Papua Collections in Western museums and to new expensive merchandise in galleries. Seen by other (Western) eyes in a different context, changes the meaning of artefacts. As a result, the artefacts have mainly become objects of art with a price tag attached to them. Unfortunately, in contrast to the Australian Aborigines, the makers of Papuan artefacts often receive too little of the proceeds of their work sold in the West.